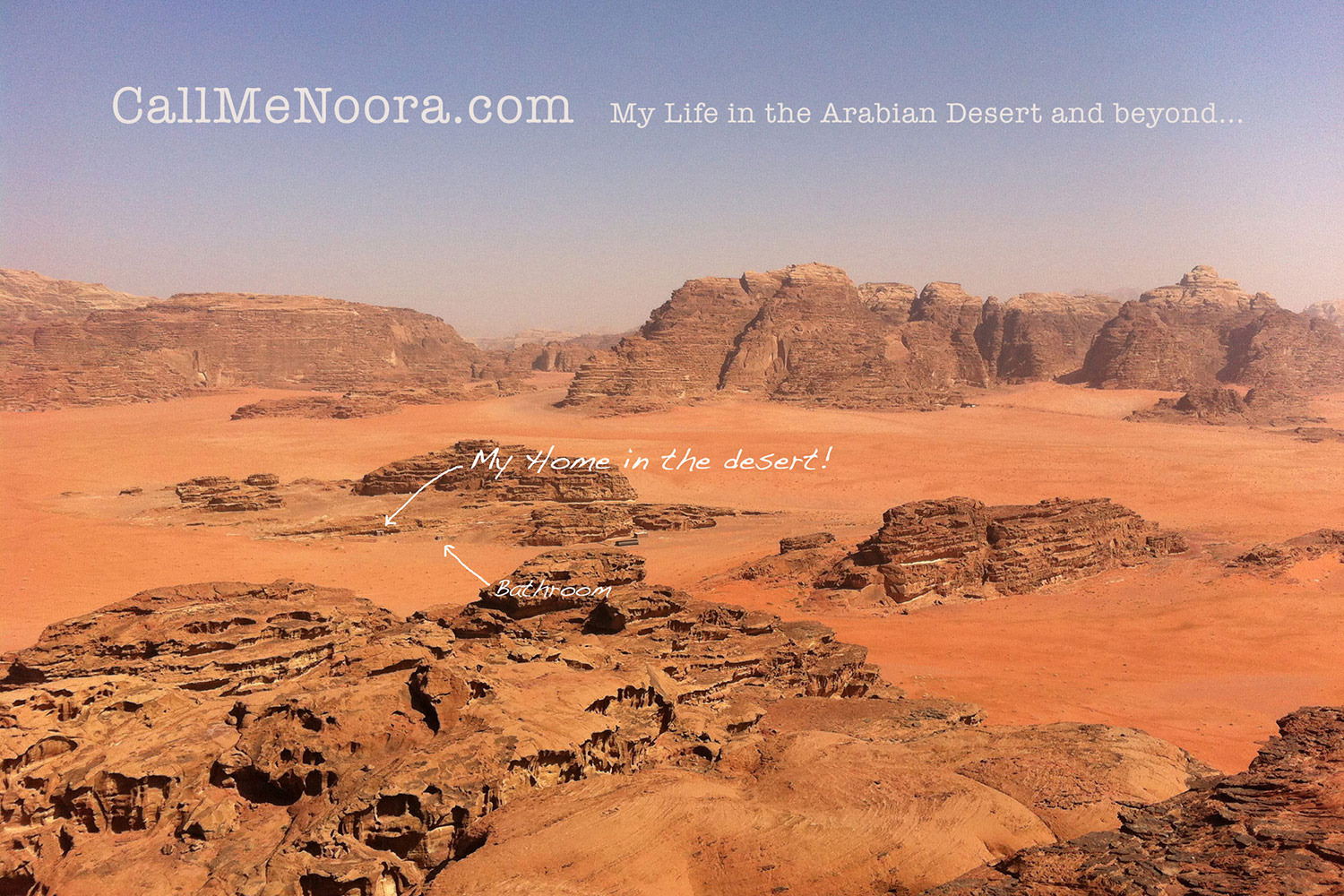

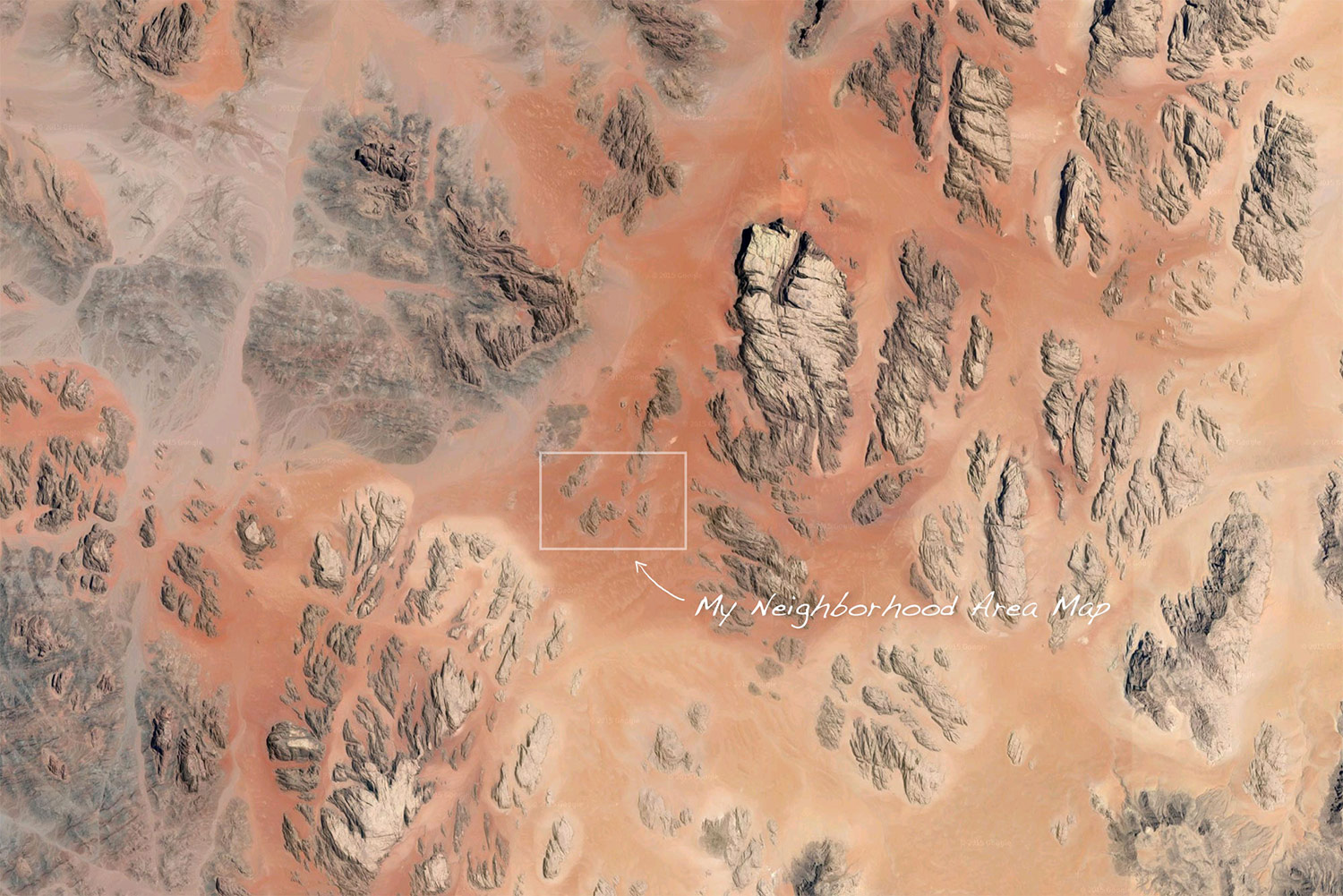

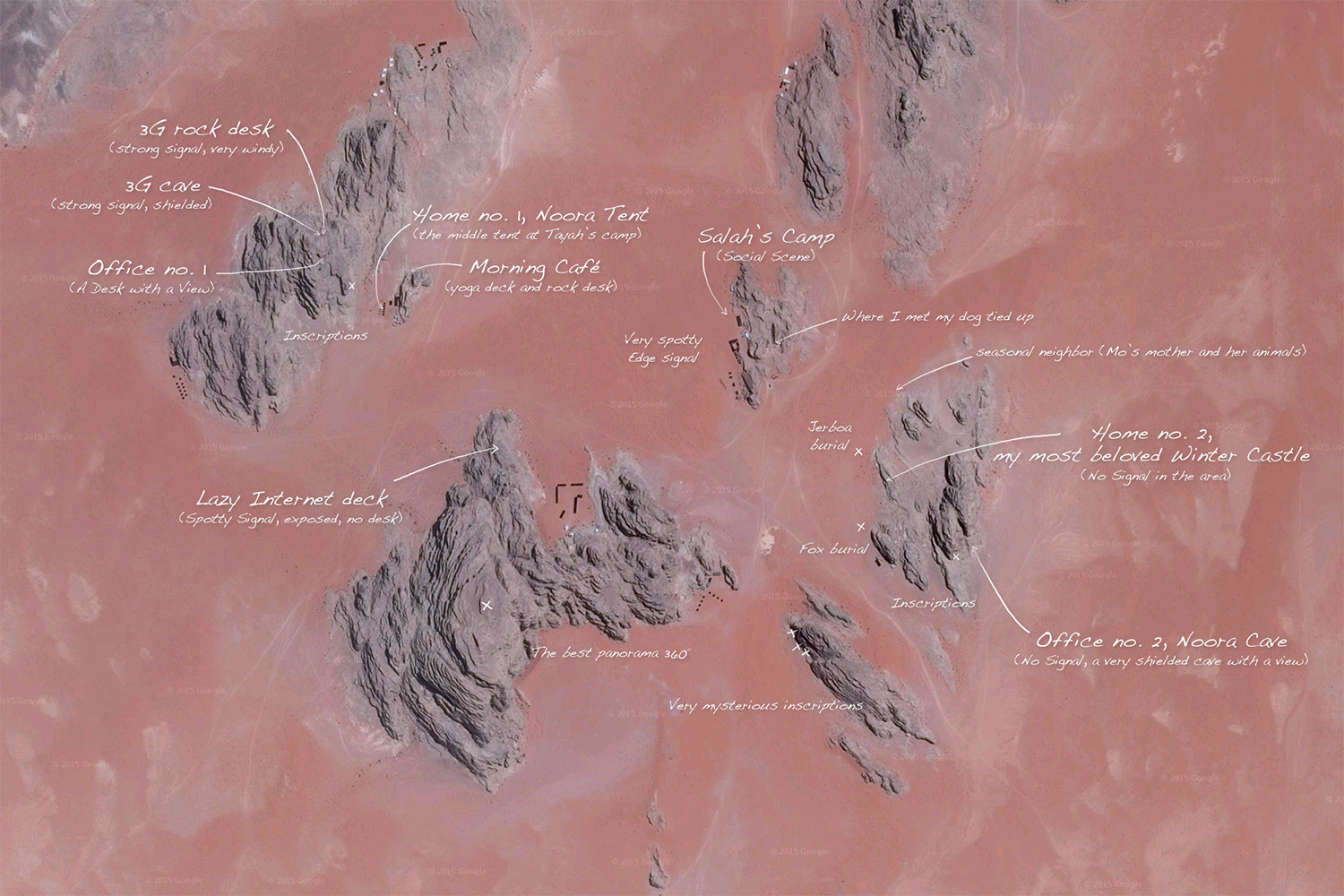

Call Me Noora is a performance and installation work that incorporates writing, photography, video, and Internet media. While living with a Bedouin family for a month in the summer of 2012, in order to take videos of herself acting as a Bedouin woman for the Desert Nomads project, Miru began making plans to lead a solitary life in the desert, with the help of Bedouin friends she had made. In the spring of 2013, she moved into the desert, at first living in a tent, and gradually making the place more habitable. By that winter of the same year, she had made the desert her main home, having completely moved all her belongings from the city to her tent. Then, after surviving the cold winter nights in a tent, she decided to move into a more permanent structure she found nearby in the desert. It was an abandoned kitchen of a tourist camp that was never built. Over time, she converted it into a comfortable bedroom, and named it Winter Castle. It became her home for the entire year. The duration of the whole process was almost two years, and the actual time spent in the wilderness was about ten months, lasting anywhere from several days to two months at a time. The only witnesses of this project were Bedouins and several tourists, an audience unaware of any performance. She also took on a pseudonym, Noora (meaning Light in Arabic), not to reveal her real identity, out of necessity due to the region's conservatism.

Towards the end of her stay, she put up a blog, Callmenoora.com, which recounts stories about her life in the Arabian desert. And during her last stay in the desert, which lasted about two consecutive months at the Winter Castle in solitude, she hiked daily to a mountain where she could find some 3G signal and uploaded photos to her Instagram account (now it's her desert dog's account @guernas, where you can scroll down and see the original posts with full captions.) Then, at the end of November 2014, she packed up her computer and a few items, and simply left, leaving most of her belongings and creations as they were. It is not known exactly what happened to her places, and mostly likely only traces and memories remain.

This project will come to a full fruition with a book, a narrative about Noora. Call Me Noora as a whole is a creative attempt at blending different genres, blurring art and life, and bringing postmodernity to primitivity, and vice versa.

Excerpt from Callmenoora.com entry from October 14, 2014

...So imagine being surrounded by sandstone formations and sand dunes created from those stones over gazillions of years. The mushroom rocks in Egypt are shaped that way, because the wind picks up sand grains only to a certain height, and where the sand hits the sandstone, the abrasion is greater. And here in this desert, the dripping shapes carved on the red sandstone mountains are created by millions of years of rain. When it rains heavily, you can see this clearly from the pattern of moving water. Sometimes you can even see the evidence that the whole desert at one point was under the sea, which was probably during the Eocene epoch, roughly 60 to 30 million years ago, way before humans came to existence. The feeling of being humbled by the grandeur of this timescale is an important element in the sublime. Some people might take it in the religious direction. God designed Earth much before he made us, and we are minuscule in the face of God all mighty. And looking up at the night sky, shimmering stars that seem to rain down on you, one cannot but imagine that there must be something beyond our human lives on Earth. It’s no surprise to me that the three big monotheistic religions all came from the desert.

In my case, reflecting on the rocks that changed shape over millions of years, and staring at the milky way–billions of stars that make up our galaxy, which is one in billions of other galaxies–have given me the exact opposite of self-insignificance. I am here, working the complex mechanism of my brain, at this precise moment, in this precise place in the universe. The improbability of this event makes it all the more special that I exist. Meditating alone here sometimes expands the self so much that I would grow as large as the desert and beyond, into the whole universe. What a big ego!

It was the wonder of being in the middle of such sublimity that made me eventually want to live in a desert. And when I began my experiment of settling here, I thought I would give up all my worldly things, such as Prada boots and Mulberry bags, to live with the minimal. I would do yoga and meditation daily, and might even starve myself to cleanse my body and soul (actually that was a bad diet plan). Then maybe I’d run into an enlightenment and re-emerge as some sort of a desert guru. This romantic idea kept me going for some time, to overcome the initial hardship in the change of environment. Being so occupied with adapting to the new life, I quickly forgot about art, also because of the beauty that was all around me. I didn’t feel the need to create, or seek what I considered as “art,” because I was living inside a masterpiece. Why would you need to hang a painting in your room, when you can simply step out and please all your aesthetic senses?

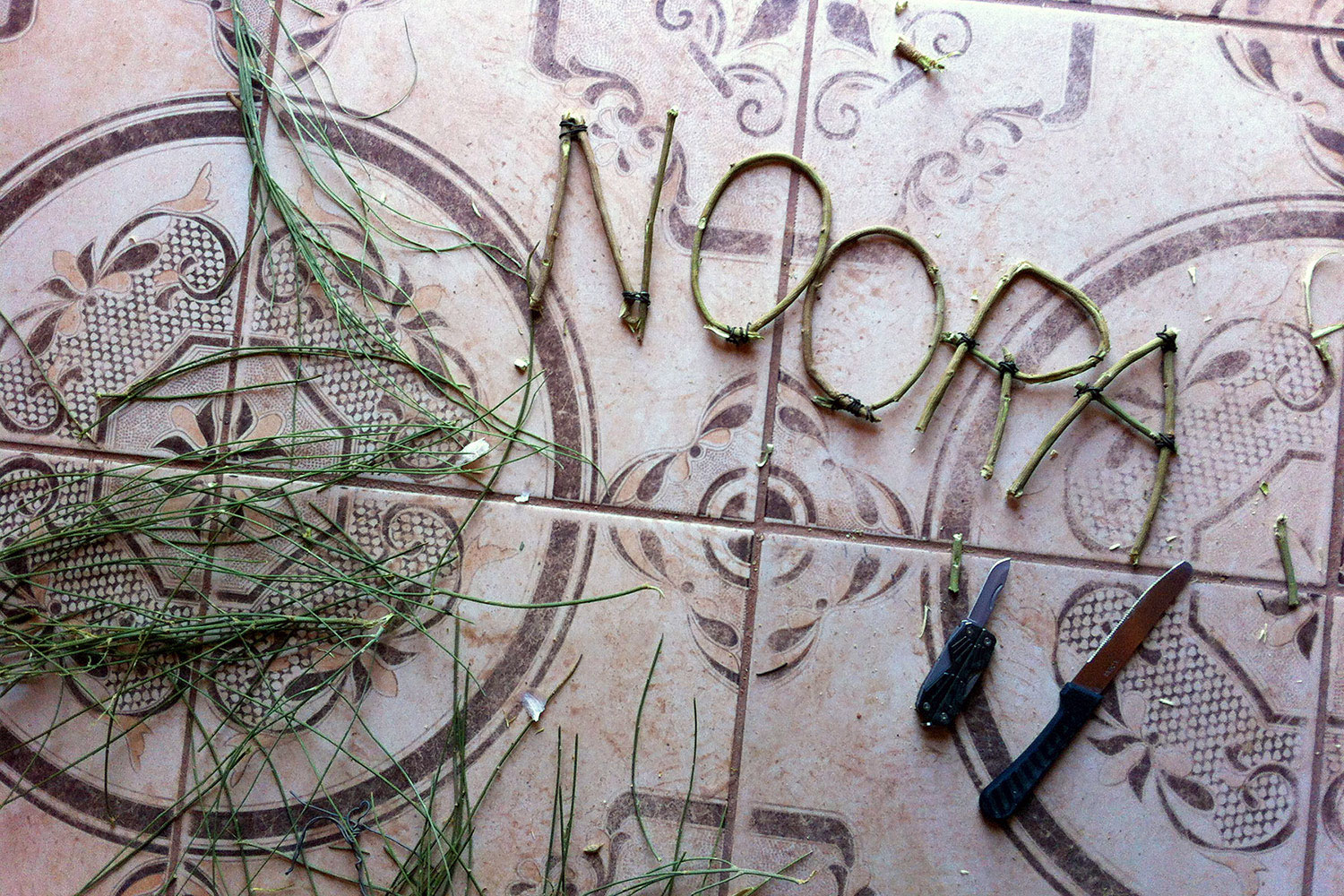

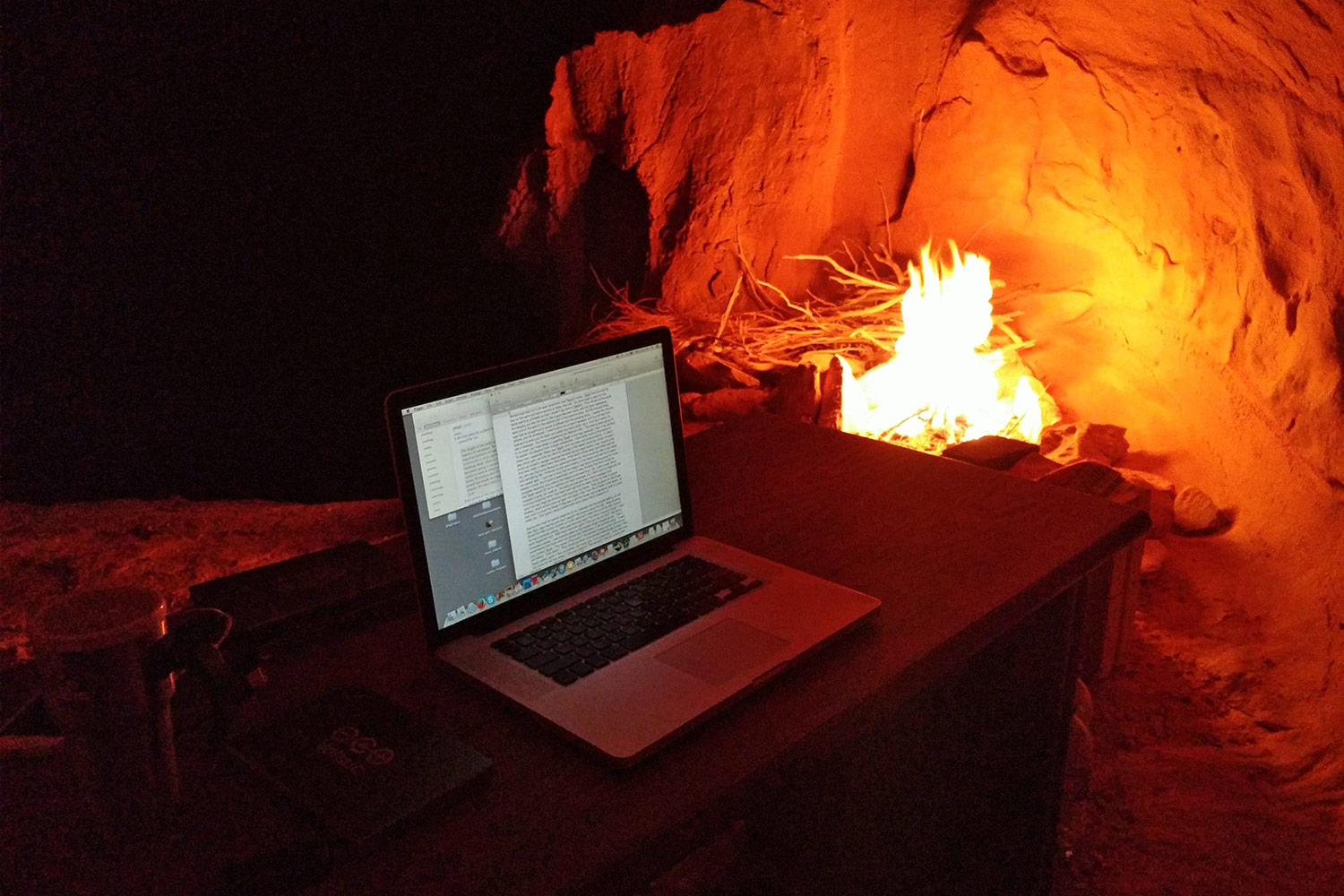

However, as I described in my previous posts, I was actually being constantly creative in the desert. I began moving rocks and making things out of available materials. The process of putting my desk–which was also for the purpose of creative work–and cleaning the area, was a lot like the process of making an artwork. Sometimes I would just stare at the floor around my desk for a long time, because sweeping the area had made it look so unnatural. So then I would bring some pebbles back, rearrange them around the floor, level the sand near the wall, spread it out carefully to make the transition between sand and pebbles look aesthetically pleasing, and so on. Doesn’t that sound a lot like making an art object? Thinking back to what I have been doing in the desert all this time, I only now realize that the reason I could stay here for so long is that I kept making something, whether it be a rock desk or a shelf in my room. The desert was a blank canvas for me. A surface that was emptied and refreshed so that I could make the initial brush strokes. It makes sense now, why I needed to move away from the city. The city had become a place that clouded my vision, a place with too many spectacles–I had come to a point where I couldn’t even distinguish art from ads.

In conclusion, my living here in the desert has not been about eliminating art. In fact, the whole stay has been a combination of performance and installation. What I’ve been making are not art objects per se, but manifestations of artistic process...

-Miru Kim